The Chinese Tang Dynasty Visual Arts Are Known for Their?

Silver wine cup, with birds and a rabbit amid scrolling found forms.

Tang dynasty art (simplified Chinese: 唐朝艺术; traditional Chinese: 唐朝藝術) is Chinese art made during the Tang dynasty (618–907). The menses saw peachy achievements in many forms—painting, sculpture, calligraphy, music, trip the light fantastic and literature. The Tang dynasty, with its capital at Chang'an (today's Xi'an), the most populous city in the globe at the time, is regarded by historians as a high point in Chinese culture—equal, or even superior, to the Han period. The Tang menstruum was considered the golden age of literature and fine art.

In several areas developments during the Tang set up the management for many centuries to come. This was especially so in pottery, with glazed plain wares in celadon green and whitish porcelaineous types brought to a high level, and exported on a considerable calibration. In painting, the period saw the superlative level of Buddhist painting, and the emergence of the landscape painting tradition known equally shanshui (mountain-water) painting.

Trading along the Silk Route of diverse products increased cultural variety in small China cities.[1] Stimulated past contact with India and the Middle East, the empire saw a flowering of inventiveness in many fields. Buddhism, originating in what is modern twenty-four hour period India around the time of Confucius, connected to flourish during the Tang period and was adopted by the imperial family, condign thoroughly sinicized and a permanent office of Chinese traditional culture. Block press made the written word bachelor to vastly greater audiences.

Culturally, the An Lushan Rebellion of 745-763 weakened the conviction of the elite,[2] and brought an end to the lavish style of tomb figures, as well as reducing the outward-looking culture of the early Tang, that was receptive to strange influences from further w in Asia. The Groovy Anti-Buddhist Persecution, in fact against all strange religions, which reached its peak in 845, had a smashing impact on all the arts, but peculiarly the visual arts, greatly reducing need for artists.

Painting [edit]

A considerable amount of literary and documentary information almost Tang painting has survived, only very few works, specially of the highest quality. There is a good deal of biographical data and art criticism, mostly from later periods such as the Ming dynasty, several centuries after the Tang; the accuracy of this needs to be considered, and much of it was probably already based on seeing copies of the art, not originals. With a very few exceptions, traditional attributions of item scroll paintings to Tang masters are now regarded with suspicion past fine art historians.

A walled-up cave in the Dunhuang (Mogao Caves) complex was discovered by Aurel Stein, which independent a vast haul, mostly of Buddhist writings, simply also some banners and paintings, making much the largest group of paintings on silk to survive. These are at present in the British Museum and elsewhere. They are non of courtroom quality, but prove a diversity of styles, including those with influences from further west. As with sculpture, other survivals showing Tang style are in Japan, though the most important, at Nara, was very largely destroyed in a fire in 1949.[3]

The rock-cutting cave complexes and royal tombs also contain many wall-paintings; the paintings in the Qianling Mausoleum are the most important grouping of the latter, mostly now removed to a museum. Not all the royal tombs have yet been opened. Court painting mostly survives in what are certainly or arguably copies from much later, such as Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy, probably a later copy of the 7th century original by Yan Liben, though the front section of the famous portrait of the Emperor Xuanzong's horse Night-Shining White is probably an original by Han Gan of 740–760.[4] Yan Liben is an example of a famous painter who was also a very of import official.

Most Tang artists outlined figures with fine black lines and used brilliant colour and elaborate detail filling in the outlines. Yet, Wu Daozi used merely black ink and freely painted brushstrokes to create ink paintings that were so exciting that crowds gathered to watch him work. From his time on, ink paintings were no longer thought to be preliminary sketches or outlines to be filled in with color. Instead, they were valued as finished works of art.

The Tang dynasty saw the maturity of the landscape painting tradition known equally shanshui (mount-h2o) painting, which became the almost prestigious blazon of Chinese painting, especially when good past amateur scholar-official or "literati" painters in ink-wash painting. In these landscapes, commonly monochromatic and sparse, the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the "rhythm" of nature.

-

-

Buddhist mural in the Bezeklik grottoes, ninth century

Pottery [edit]

Chinese ceramics saw many significant developments, including the first Chinese porcelain meeting both Western and Chinese definitions of porcelain, in Ding ware and related types. The earthenware Tang dynasty tomb figures are amend known in the W today, but were only made to placed in elite tombs close to the capital letter in the n, between near 680 and 760. They were perchance the last significant fine earthenwares to be produced in China. Many are lead-glazed sancai (3-color) wares; others are unpainted or were painted over a slip; the pigment has now oft fallen off.

Sancai was also used for vessels for burial, and maybe for use; the glaze was less toxic than in the Han, but perhaps all the same to exist avoided for use at the dining table. The typical shape is the "offer tray", a round or round and lobed shape with geometrically regular floral-type decoration in the centre.

In the southward the wares from the Changsha Tongguan Kiln Site in Tongguan are significant as the first regular use of underglaze painting; examples take been found in many places in the Islamic world. Withal the production tailed off and underglaze painting remained a minor technique for several centuries.[5]

Yue ware was the leading high-fired, lime-glazed celadon of the flow, and was of very sophisticated design, patronized by the courtroom. This was also the case with the northern porcelains of kilns in the provinces of Henan and Hebei, which for the first fourth dimension met the Western besides equally the Eastern definition of porcelain, being a pure white and translucent.[6] One of the outset mentions of porcelain by a foreigner was in the Chain of Chronicles written by the Arab traveler and merchant Suleiman in 851 AD during the Tang dynasty who recorded that:[7] [eight]

They take in China a very fine dirt with which they brand vases which are every bit transparent every bit glass; water is seen through them. The vases are made of clay.

The Arabs were well used to glass, and he was sure that the porcelain that he saw was not that.

Yaozhou ware or Northern Celadon also began under the Tang, though like Ding ware its best period was under the side by side Song dynasty.

-

Yue ware vase with incised ornament, c. 900, "green-glazed porcelaneous stoneware"

-

"Offer plate" with sancai glaze, 8th century.

-

"Offer plate" with sancai coat, decorated with a bird and trees, 8th century.

-

"Offering plate" with sancai with six eaves and "three colors" glaze, 8th century.

-

Tomb figures: three of viii lady musicians on horseback, early 8th century

-

Ladies dancing, 7th century

-

Tomb effigy of a plump Tang woman

-

Tomb figure of a foreigner with a wineskin, c. 674–750

-

Tomb figure, 7th-eighth century

-

Tomb figure of a Sogdian man wearing a distinctive cap and face veil, maybe a camel rider or even a Zoroastrian priest engaging in a ritual at a burn temple, eighth century AD

Sculpture [edit]

Most sculpture before the official rejection of Buddhism in 845 was religious, and a vast amount was destroyed during the Tang menstruum itself, with virtually of the remainder lost in later periods. In that location were many statuary and wooden sculptures, whose style is best seen in the survivals in Japanese temples. Awe-inspiring sculpture in stone, and also terra cotta, has survived at several complexes of rock-cut temples, of which the largest and almost famous are the Longmen Grottoes and the Mogao Caves (at Dunhuang), both of which were at their peak of expansion during the Tang. The best combined "the Indian feeling for solid, swelling form and the Chinese genius for expression in terms of linear rhythm ... to produce a style which was to become the basis of all later Buddhist sculpture in Cathay."[nine]

The tomb-figures are discussed above; though probably not treated very seriously every bit fine art by their producers, and sometimes rather sloppily made, and peculiarly painted, they remain vigorous and effective equally sculpture, especially when animals and foreigners are depicted, the latter with an chemical element of caricature. A rather dissimilar class and type of tomb sculpture is seen in the reliefs of the half-dozen favourite horses at the mausoleum of Emperor Taizong (d. 649). By tradition these were designed by the court painter Yan Liben, and the relief is so flat and linear that information technology seems likely they were carved after drawings or paintings.[10]

-

-

Tang dynasty bodhisattva statue missing its head and left arm

-

A limestone statue of a mourning attendant, 7th century

-

Metalwork and decorative arts [edit]

Tang elite metalwork, surviving mostly in statuary or silver cups and mirrors, is often of superb quality, decorated using a variety of techniques, and often inlaid with gold and other metals. An exceptionally fine deposit is the collection in the Tōdai-ji in Nara in Japan of the personal appurtenances of Emperor Shōmu, given to the Buddhist shrine by his girl Empress Kōmyō subsequently her father's death in 756. Equally well as metalwork, paintings and calligraphy, this includes article of furniture, glass, lacquer and wood pieces such as musical instruments and board games. About is probably made in China, though some is Japanese and some from the Center East.[11]

Another of import eolith was discovered in 1970 at Eleven'an when the Hejia Village hoard was uncovered past construction. Placed into two large ceramic pots, 64 cm high, and a silver i, 25 cm loftier, this was a large collection of over a thousand objects, birthday representing a rather puzzling collection. Several of them were aureate or silver vessels and other objects of the highest quality, as well every bit hardstone carvings in jade and agate, and gemstones. It was probably hidden in a bustle during the An Lushan defection, in which the Tang upper-case letter was taken more than once. Many of the objects are imported, generally from along the Silk Road, especially Sogdia, and others show Sogdian influence.[12] Two objects from the hoard (illustrated) are included on the very select official list of Chinese cultural relics forbidden to be exhibited abroad. The hoard is at present in the Shaanxi History Museum.

-

Gilt hexagonal silvery plate with a Fei Lian beast blueprint

-

-

Mirror with floral medallion, plant sprays, birds, and insects, 7th century

Architecture [edit]

There had been an enormous amount of building of Buddhist temples and monasteries, but in 845 these were all confiscated past the government, and the great majority destroyed. The normal construction material for buildings other than towers, pagodas, and military works in the Tang was even so wood, which does not survive very long if not maintained.[xiii] The rock-cut architecture of the famous surviving sites of course survives neglect far better, only the Chinese more often than not left the external facades of cavern-temples unornamented, dissimilar the Indian equivalents at sites like the Ajanta Caves.

Two large Tang pagodas survive in the capital, now 11'an, which otherwise has few remains dating back to the Tang. The oldest is the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, rebuilt in 704 in brick, and reduced in height after harm in the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake. The Modest Wild Goose Pagoda was also rebuilt in 704, but merely lost a few metres in the earthquake. Some Tang pagodas tried to reconcile the course with the Indian shikara temple tower, or even had a stupa every bit function of the superstructure; the Tahōtō at the Ishiyama-dera temple in Japan is a surviving later on example, with a roof on top of the stupa.[14]

The main hall of the relatively pocket-sized rural Nanchan Temple has a main structure of wood. Much of it appears to have survived from the original construction in 782, and it is recognised every bit the oldest wooden edifice in China. The tertiary oldest is the chief hall of the nearby Foguang Temple of 857.[15]

Both are studied for their dougong bracketing systems, joining the roof to the walls. These complicated arrangements persisted until the finish of traditional Chinese architecture, but are often considered to have reached a meridian of elegance and harmony in the Song and Yuan dynasties, before condign over-elaborate and fussy. The Tang examples show an increase in complexity before the corking periods, and the beginnings of the uplift at the edges of roof lines that was to grow stronger in later periods. Japan has preserved rather more temple halls built in very like styles (or in many cases has carefully rebuilt them as verbal replicas over the centuries).[xvi]

-

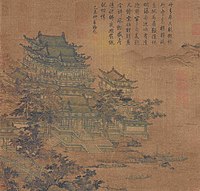

Luoyang Pavilion by Li Zhaodao (fl. early 8th c.)

-

-

-

The Nine Tiptop Pagoda of Shandong, completed by 756 and crowned with an unusual set of miniature pagodas; it is besides unique for its octagonal, rather than square, base plan.

-

Music [edit]

The first major well-documented flowering of Chinese music was for the qin during the Tang dynasty, though the qin is known to accept been played since earlier the Han dynasty.

Belatedly 20th century excavations of an intact tomb of the menses revealed non only a number of instruments (including a spectacular concert bell set) but as well inscribed tablets with playing instructions and musical scores for ensemble concerts, which are now heard again as played on reproduction instruments at the Hubei Provincial Museum.

Opera [edit]

Chinese opera is generally dated back to the Tang dynasty with Emperor Xuanzong (712–755), who founded the Pear Garden, the first known opera troupe in China. The troupe mostly performed for the emperors' personal pleasure.

Poetry [edit]

The verse of the Tang dynasty is peradventure the most highly regarded poetic era in Chinese poetry. The shi, the classical grade of poetry which had developed in the late Han dynasty, reached its zenith. The anthology Three Hundred Tang Poems, compiled much later, remains famous in Cathay.

During the Tang dynasty, poetry became popular, and writing verse was considered a sign of learning. One of Prc's greatest poets was Li Po, who wrote about ordinary people and about nature, which was a powerful forcefulness in Chinese art. One of Li Po's brusk poems, "Waterfall at Lu-Shan", shows how Li Po felt most nature.

Tang dynasty artists [edit]

- Bai Juyi (772–846), poet

- Zhou Fang (730–800), painter, besides known as Zhou Jing Xuan and Zhong Lang

- Cui Hao (?–754), poet

- Han Gan (718–780), painter

- Zhang Xuan (713–755), painter

- Du Fu (712–770), poet

- Li Bai (701–762), poet

- Meng Haoran (689 or 691–740), poet

- Wang Wei (699–759), poet, musician, painter

- Wu Tao-Tzu (680–740), famous for the myth of entering an fine art work

- Zhang Jiuling (678–740), poet

See as well [edit]

- Chinese art

- Qianling Mausoleum

Notes [edit]

- ^ Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Fine art : guide to the drove. [Birmingham, Ala]: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 24. ISBN978-ane-904832-77-5.

- ^ Sullivan, 145

- ^ Sullivan, 132-133

- ^ Sullivan, 134-135

- ^ Vainker, 82–84

- ^ Vainker, 64–72

- ^ Temple, Robert Yard.G. (2007). The Genius of Cathay: three,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention (third edition). London: André Deutsch, pp. 103–6. ISBN 978-0-233-00202-six

- ^ Bushell, S. Westward. (1906). Chinese Art. Victoria and Albert Museum Art Handbook, His Majesty's Stationery Role, London.

- ^ Sullivan, 126-127, 127 quoted

- ^ Sullivan, 126

- ^ Sullivan, 139-140

- ^ Hansen, 152-157; Sullivan, 139

- ^ Sullivan, 123-124

- ^ Sullivan, 125-126

- ^ Sullivan, 124

- ^ Sullivan, 124-125

References [edit]

- Hansen, Valerie, The Silk Road: A New History, 2015, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0190218428, 9780190218423, google books

- Sullivan, Michael, The Arts of Prc, 1973, Sphere Books, ISBN 0351183345 (revised edn of A Short History of Chinese Fine art, 1967)

- Vainker, S.J., Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, 1991, British Museum Printing, 9780714114705

Further reading [edit]

- Watt, James C.Y.; et al. (2004). Prc: dawn of a golden age, 200-750 AD . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN1588391264.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tang_dynasty_art

0 Response to "The Chinese Tang Dynasty Visual Arts Are Known for Their?"

ارسال یک نظر